A double whammy! Quantifying AND cleaning fusion fuel from a fusion reactor wall.

The question

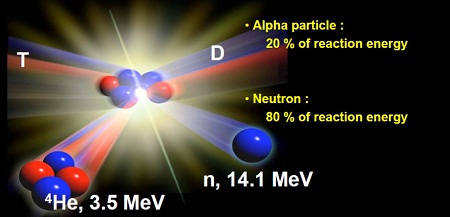

A massive challenge of future fusion reactors is to keep the walls of the reactor clean. The fuel to be used for magnetic fusion power generation will be isotopes of hydrogen called deuterium (nucleus consists of a proton and neutron) and tritium (a proton and two neutrons), which will be heated to extreme temperatures and confined in the plasma state. At sufficient temperature, density, and confinement duration, deuterium and tritium will fuse together to form helium and a fast neutron, which will carry excess energy to be harnessed for electricity generation.

Deuterium and tritium plasma ions can become stuck in the reactor wall either through direct implantation or by being deposited along with plasma-eroded wall material (so-called codeposits). Well, it turns out that tritium is extremely rare. Only a few tens of kilograms exist on earth and it’s one of the most valuable substance in the world by weight at about $30k per gram. In addition, since tritium is radioactive there are regulatory limits on the amount of tritium that can be trapped in the walls of a reactor vessel.

For these reasons, in-vessel strategies to accurately measure trapped tritium will be needed to determine where the tritium is hiding. The ability to remove trapped tritium will be essential to keep the total amount below regulatory licensing requirements, and recovering the trapped tritium will be needed to maintain sufficient plasma tritium for fusion reactions and power generation.

Enter laser-induced desorption spectroscopy (LIDS), which serves the dual purpose of both measuring (via optical emission spectroscopy) and removing (via thermal desorption) trapped tritium.

The method

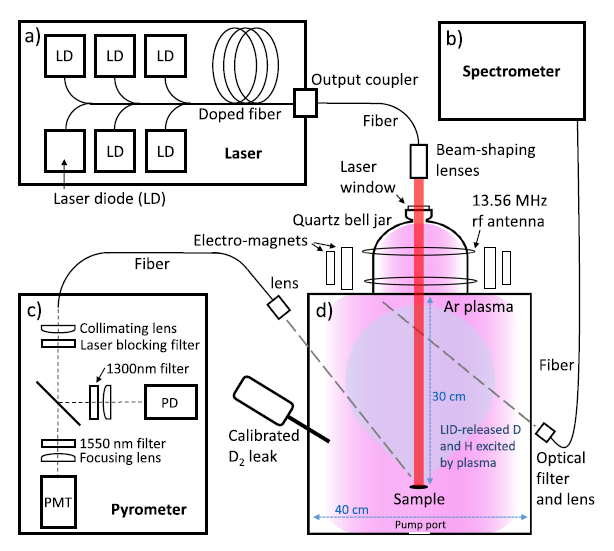

To develop LIDS technology, titanium-deuterium (Ti-D) and tungsten-deuterium (W-D) codeposit layers were created by magnetron sputtering. The codeposited samples were immersed one at a time in an inductively coupled RF argon plasma, and a high power laser was used to quickly heat the samples with a 1 second pulse width during LIDS. Electrons in the background argon plasma ionized, dissociated, and excited laser-desorbed deuterium, which was measured with an optical spectrometer using Balmer series Dα and Hα emission. A fast pyrometer monitored the sample surface temperature during laser induced desorption. Figure 1 shows the experimental setup of the laser, plasma chamber, spectrometer, pyrometer, and calibrated deuterium gas source for calibration.

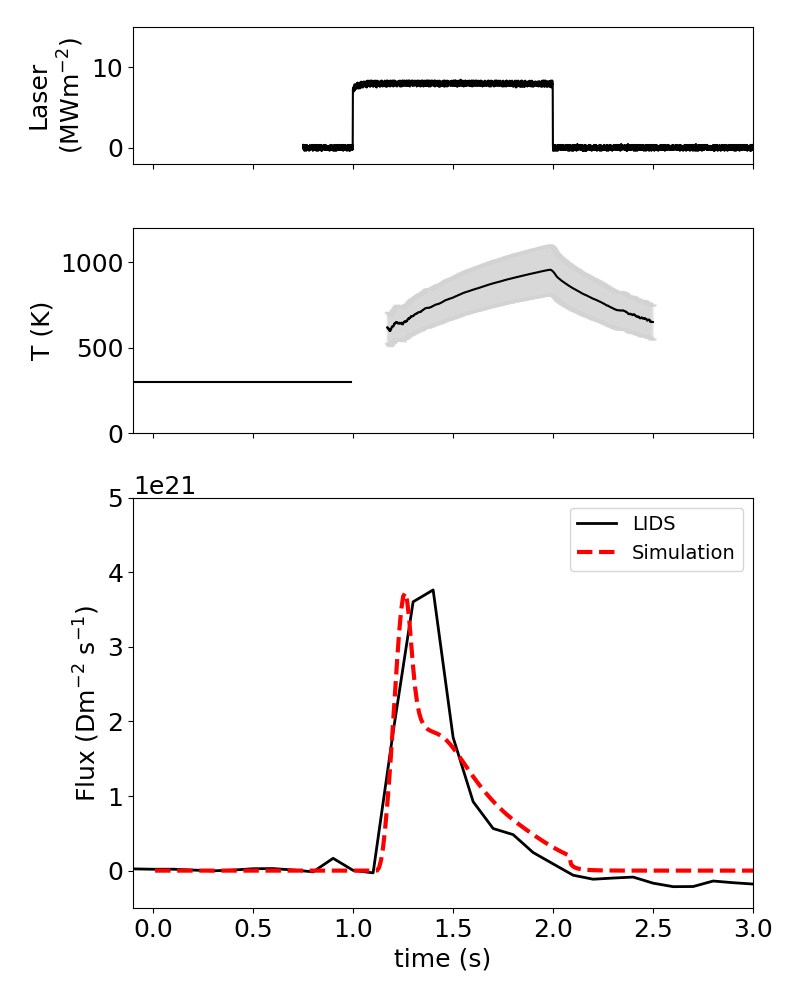

I used a couple of tricks in order to accurately measure the time evolution and quantity of the released deuterium during laser heating. The first was to isolate the deuterium and hydrogen spectral lines, which was done using a special form of spectral fitting. The second trick was to apply a signal processing technique called deconvolution to the spectroscopic measurements. This was needed to correct for system-level time-dependent effects that arose from the interaction of released deuterium with the vessel walls and due to finite vacuum pumping speed. Deconvolution is a powerful inverse filtering technique used in many fields when overlapping signals need to be separated. The overlap could be in the time, frequency, or spatial domain.

The results

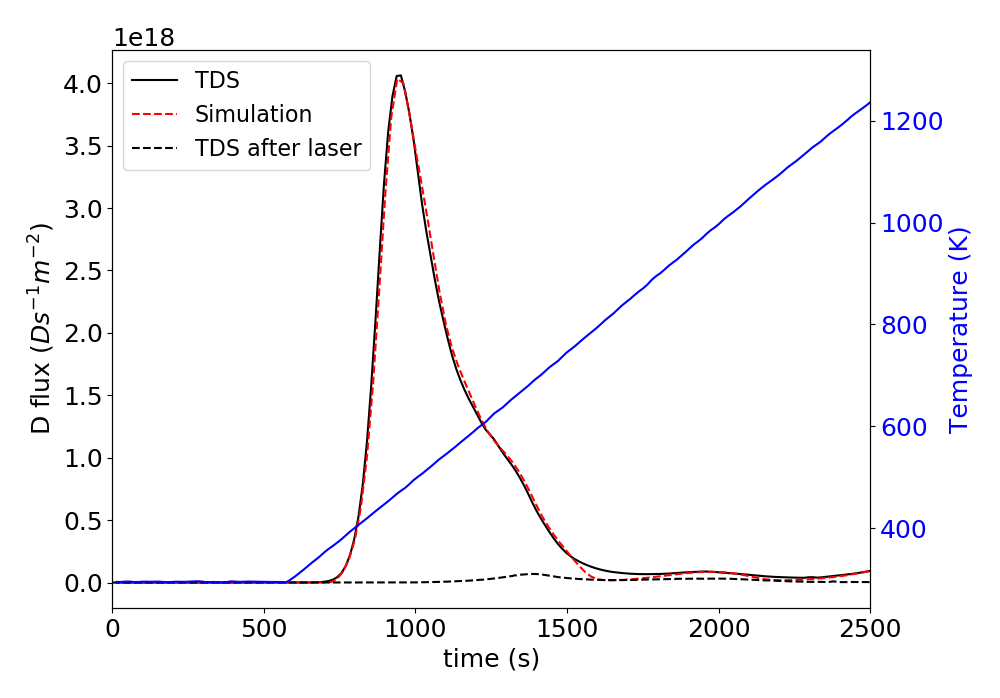

The gold standard for measuring the quantity of trapped hydrogen in materials is thermal desorption spectrometry (TDS), also called temperature programmed desorption (TPD). In TDS, material is slowly heated so that the thermal energy of hydrogen exceeds the detrapping energy, and desorbed hydrogen is measured with a mass spectrometer. Figure 2 shows the result of TDS on one of the samples with no laser heating. A diffusion-reaction model was used to fit the data to determine hydrogen trapping and other parameters in the material. This same model was applied to the LIDS data with no adjustments, and agreed quite well with the deconvolved LIDS measurements as shown in Figure 3.

TDS was performed on a sample after LIDS to check if there was any deuterium remaining in the sample after a single 1 second laser pulse with power density of 8 MW/m2. Figure 2 shows that all deuterium was removed by the laser, which is an important check in order to have confidence in the inferred retention values.

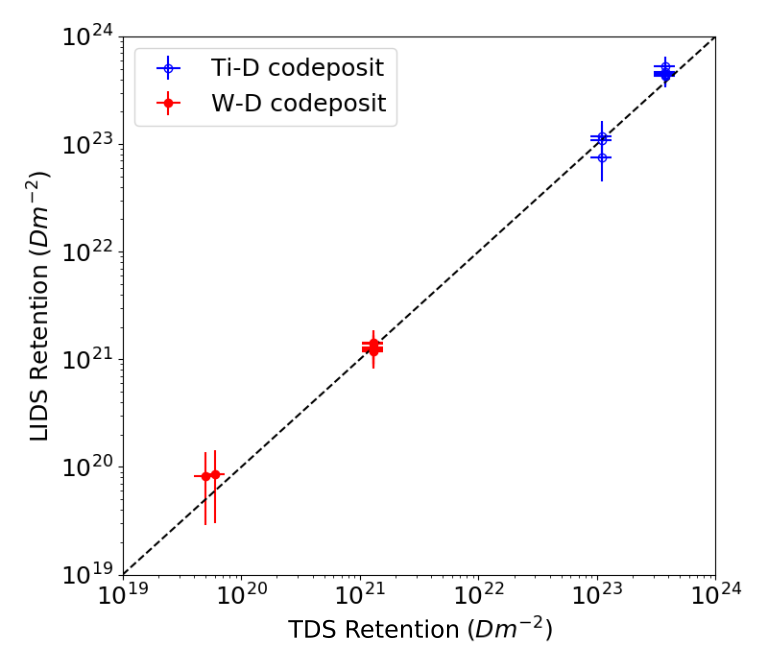

An additional verification of the quantitative accuracy of LIDS measurements is seen in Figure 4, which shows agreement between LIDS and TSD over nearly four orders of magnitude in measured areal deuterium retention. This agreement unequivocally demonstrates the viability of calibrated LIDS as a hydrogen isotope inventory measurement and removal diagnostic tool.

Who cares?

My development of LIDS is important because this method can provide time-resolved measurements of tritium trapped in materials of future fusion reactors. A scanning laser could potentially use LIDS technology to locate and remove trapped tritium in the reactor walls. The method can be deployed in-situ and without the need to remove sections of the vessel wall, bringing fusion one step closer to reality (there are many steps, unfortunately).

This work was published, selected as Editor’s Pick, and highlighted on the journal’s website at Review of Scientific Instruments.