Predicting the impact of hot plasma on materials. Or, how to not break a fusion reactor.

The question

Plasma instabilities in a fusion power plant will heat material surfaces up to their melting point and beyond, leading to potential mechanical failure and radical changes to thermomechanical properties. Thermal testing of materials is usually done off-line using lasers or electron beams to simulate plasma instabilities, by matching certain parameters such as energy density and pulse width. However, these heat sources usually do not match the temporal (time) shape of the actual plasma instabilities, which caused me to question how the temporal shape of the heat pulse affects the extent of material damage and peak surface temperature reached during the pulse. Some people thought I was wasting my time because after all, doesn’t conservation of energy say that the energy per pulse is what matters in terms of material heating?

The results

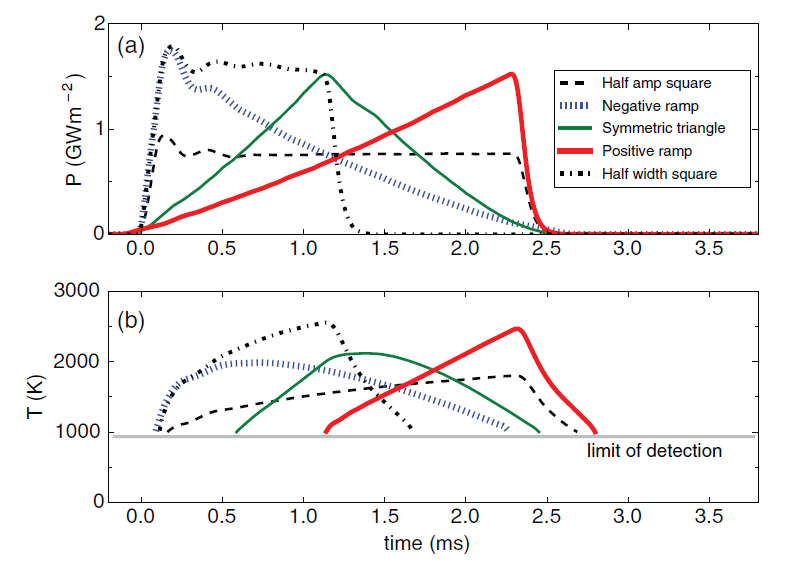

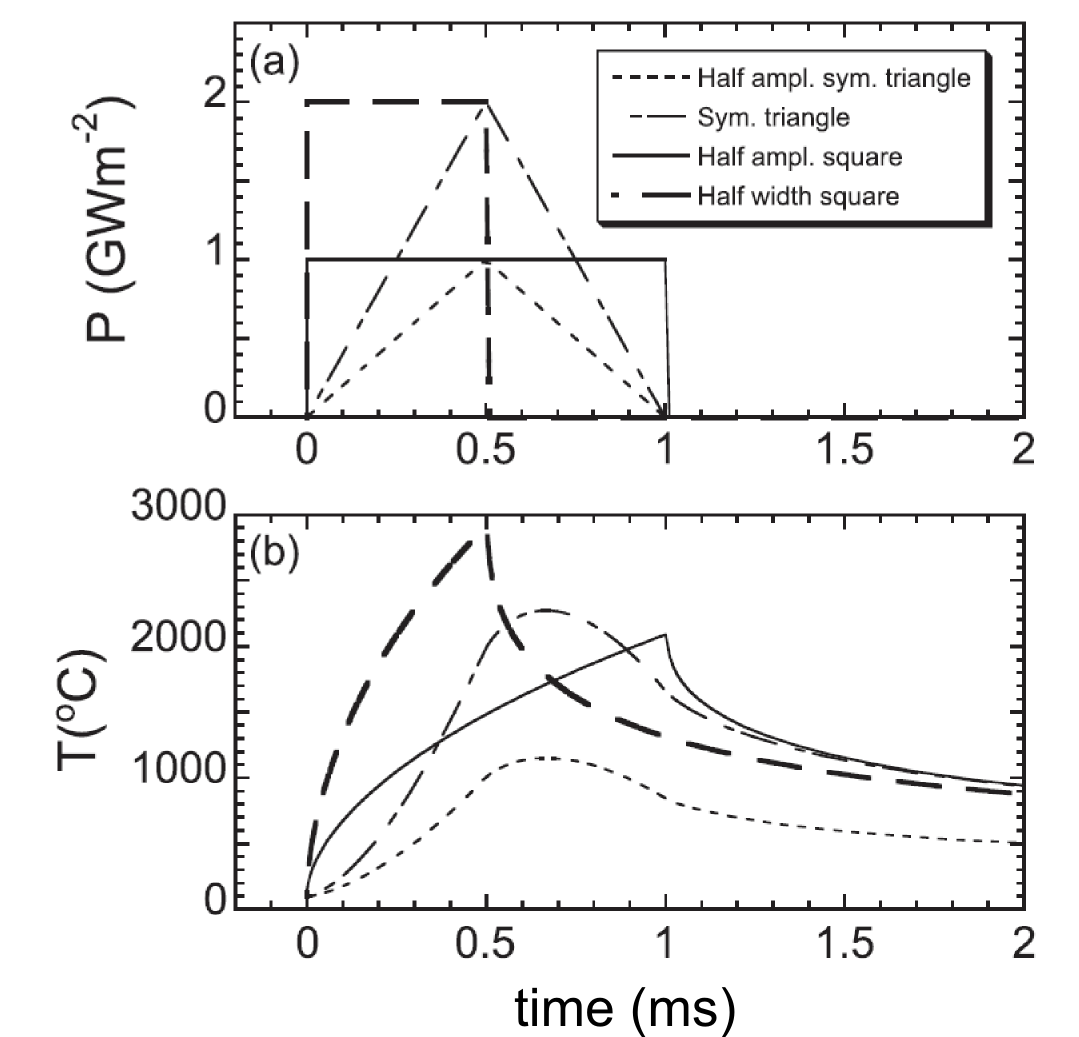

Actually, the temporal shape does have a significant effect due to the diffusive nature of heat flow into the material.Pulses with the same peak power, same energy per pulse, and same pulse width can cause different peak temperatures! For Figures 1 and 2, I programmed a laser with different temporal pulse shapes and fired the laser at tungsten, a leading material for future fusion reactors, in order to simulate heating from plasma instabilities. In Figure 3, the surface temperature calculated from computer simulations of heating diffusing into the material are shown. These data show that the maximum surface temperature is not the same for the pulses, despite the fact that all the pulses have the same power density and pulse widths. In fact, the difference in peak surface temperature is up to 40%, which may mean the difference between successful operation and possible catastrophic failure of the material. The surface temperatures were measured optically using a high speed pyrometer that I designed and built.

Who cares?

This work is important because predicting the impact of powerful heat pulses from a fusion plasma is critical to the success and survivability of a fusion power facility. It turns out that plasma instabilites typically have a unique temporal shape, and if the shape is not properly considered during material testing and numerical modeling, all bets are off in terms of predicting what will happen in an actual fusion reactor. The biggest risk is cracking of the wall material, which can lead to a coolant leak, major damage to the reactor vessel, and prolonged reactor shutoff for repairs.