Vorticity wave echoes: the illusion of time reversal

The question

Why does time have an arrow? After all, nearly all the laws of physics are time-reversible, that is, the equations of motion are valid if you run time forward or backward. Nothing in classical physics prevents a series of events running in reverse. For example, if you drop a wine glass on the floor and it shatters into little pieces, physics describes the motion of all the atoms equally well for either direction of time. On a macroscopic level, entropy (disorder) increases after the glass breaks, but there is still no physical law preventing all the little pieces reforming a whole glass again. This reversal is extremely unlikely because all the particles would need to follow exact trajectories in phase space, but it is possible. So based on classical physics, there is no preferred direction for the flow of time!

Why then does time move inexorably forward? Well, this is a deep question and some of the greatest minds in history have tried to explain it. One idea from Boltzmann is called molecular chaos, which states that due to uncertainty from chaos, particles forget that their velocities came from prior collisions. This assumption led to Boltzmann’s H-theorem, which predicts an increase in entropy until equilibrium is reached. Entropy does increase and this corresponds to our everyday notion of time moving in one direction. But the assumption of molecular chaos remains unproven and may not be true. In fact, Loschmidt objected to Boltzmann’s idea because it describes an irreversibe process (increase in entropy) from time-symmetric collision events. Other formalisms dealing with time’s arrow and the second law of thermodynamics include the Poincaré recurrence theorem, and a crazy hypothetical thing called Maxwell’s demon.

The results

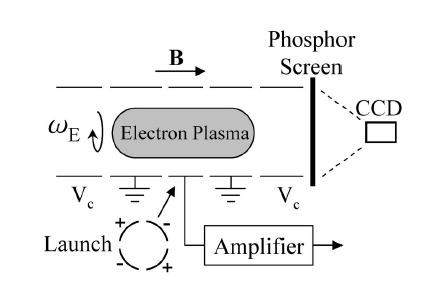

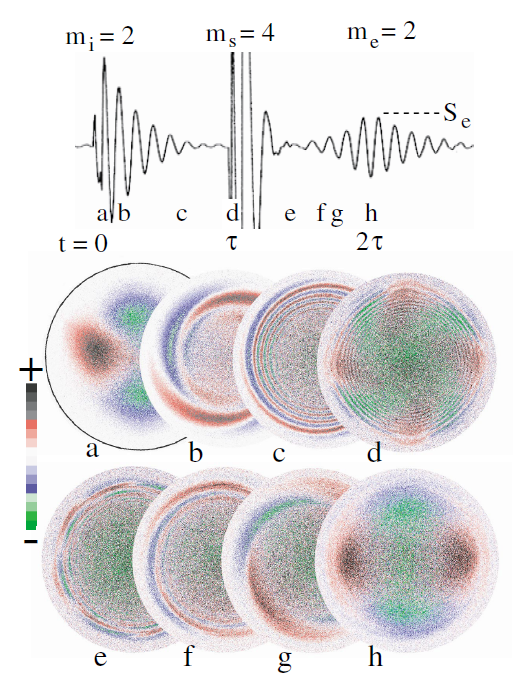

Let’s move on to what I did: for the first time ever, I explicity demonstrated reversible wave damping in a pure electron plasma and an ideal inviscid fluid. The experiments were performed in a cylindrical electron trap with controlled voltages on the end cylinders, which prevented the electrons from escaping. The collective dynamics of the electrons were dominated by 2-dimensional rotating motion around the axis of the cylinder due to ExB drifts. At a chosen time in the experiment, one of the end cylinders was grounded which allowed the electrons to freely flow along the magnetic field lines and slam into a phosphor screen (like an old TV). I used a camera to take an image of the glowing phosphor screen, and the intensity of light was proportional to the electron density. By creating the same initial plasma and holding it for different durations, a movie was created. To launch the plasma wave, the electron column was distorted in a controlled way by applying voltage to sectored cylinders, resulting in a surface wave rotating on the electron column.

These waves are identical to vorticity waves in a 2-dimensional fluid (also called Kelvin waves). My demonstration of reversibility is both beautiful and intriguing, largely because there are so few examples of reversibility in nature (yet as we know, physical equations of motion are reversible). In the case of vortex waves, the wave information is stored in a spiral structure within the electron cloud. Surprisingly, by launching a second wave with a shorter wavelength, this information is recovered by “unwinding” the spiral, resulting in the spontaneous appearance of a third wave which is the echo.

Who cares?

Since phase information must be retained in order for the echo to appear, the echo is a sensitive diagnostic for any process that destroys coherence. There is an analogy between the many-electron system I used for vorticity echoes and other many-bodied systemes, including quantum systems. Quantum computers rely on quantum coherence in order to properly execute information processing (i.e., in order to properly be a computer), but in reality a quantum system is never perfectly isolated from its environment. Quantum decoherence describes this leaking of information to the environment and it’s one of the main obstacles that prevents you from having your own personal quantum computer. Well, you can get this 2-qubit toy, but a commercial quantum computer with 50 or so qubits would set you back about $10 million. The price scales not only with the number of qubits but also with the quantum computer’s ability to maintain coherence.

It turns out that my work is similar to the Loschmidt echo, which has the potential to measure the fidelity of a physical system used for quantum computing. And measuring is the first step to creating new ways to mitigate the problem of decoherence.

My work was published and highlighted on the webpage of the premier physics letter journal Physical Review Letters, and also published in Physics of Plasmas.